Written By: dr. Aisha Savannah

Supervised By: dr. Jeffrey Giantoro, Sp. DVE

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) refers to a group of rare, genetically determined skin disorders characterized by recurrent blistering, erosions, ulcerations, and chronic open wounds. These manifestations result from genetically mediated defects that cause skin fragility within the dermo-epidermal junction.1 On a molecular level, pathogenic variants affect genes encoding proteins essential for epidermal–dermal adhesion and structural stability.2 Clinically, children affected by EB have skin as delicate as a butterfly’s wing—hence the term “the butterfly children”.3

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) affects approximately 50 per one million live births, with around 500,000 cases reported worldwide. The prevalence appears consistent across countries and ethnic groups.3 EB is classified into four major subtypes: Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex (EBS), Junctional EB (JEB), Dystrophic EB (DEB), and Kindler EB (KEB), with EBS accounting for about 70% of all cases.1 The incidence of all types of dystrophic EB (DEB) in the United States is approximately 6.5 per million live births, with an estimated global prevalence of around 500,000 individuals.4

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) typically manifests at birth or during early childhood. The common clinical features include blistering, skin fragility, and chronic non-healing wounds that are disproportionate to minor mechanical trauma. A family history revealing similar manifestations may be observed. Pain and pruritus are also frequent accompanying complaints. Lesions predominantly occur at sites exposed to pressure and friction, most commonly the hands, feet, buttocks, and knees. In neonates and infants, the diaper area is often affected as well.5 Cases diagnosed later in life generally represent milder or localized EB subtypes.6 Clinical manifestation of EB could be seen in Figure 1.

Subtle phenotypic differences are often difficult to distinguish through clinical examination alone. A definitive diagnosis requires specialized investigations, including electron microscopic examination of skin biopsy specimens, immunofluorescence microscopy, genetic mutation analysis, and antigen mapping. These modalities also enable precise classification of the EB type and subtype.1,8 Certain classical subtypes can be readily recognized, such as1:

- Localized epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS): characterized by acrally distributed blistering with accompanying keratoderma.

- Severe EBS: presents with confluent palmoplantar keratoderma and clustered, arcuate, herpetiform blisters.

- Junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB): typically seen in neonates presenting with a hoarse cry, overgranulation in the perioral, neck, and axillary regions, and tooth enamel defects.

- Severe dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB): marked by extensive scarring leading to microstomia, loss of lingual papillae, digital contractures, and pseudosyndactyly.

- Kindler epidermolysis bullosa (KEB): distinguished by photosensitivity and the presence of poikiloderma.

Given its genetic etiology, molecular genetic testing plays a crucial role in confirming the specific subtype of epidermolysis EB. Genetic counseling, along with prenatal and preimplantation screening, is essential to assess the risk of transmission to offspring.1,8

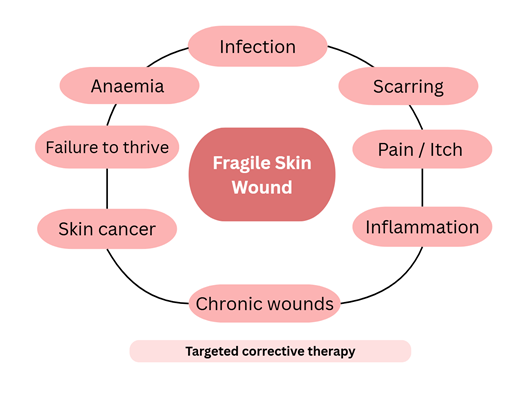

The management of EB focuses on early and accurate diagnosis, prognosis counseling, symptom relief, enhancement of quality of life, prevention of complications, and ongoing genetic guidance. Depending on disease severity, patients should undergo regular follow-up—at least annually—in coordination with their primary care clinician. A comprehensive skin examination, including photographic documentation of suspicious lesions, is recommended for disease monitoring.1 Emerging treatment approaches include gene-targeted therapies (Figure 2).2

As there is currently no definitive cure for EB, management remains primarily palliative. The main objectives of treatment are to alleviate symptoms, which can often be debilitating, and to enhance patients’ quality of life. Therapeutic efforts focus on protecting the skin, promoting wound healing, and minimizing the risk of infection while maintaining optimal comfort. Individuals with EB generally experience greater comfort in cool environments, with protection from ants and other insects, and when seated on soft, non-abrasive surfaces—such as beanbag chairs—that minimize friction and shear forces on their fragile skin.9

Dressing management in EB simplex focuses on preventing infection, cooling the blister sites and protecting the skin from trauma. The most effective management is lancing the blisters.10 Pain treatment for children with EB involves a multi-faceted approach, including standard systemic analgesics like acetaminophen and opioids, as well as localized treatments such as topical lidocaine or botulinum toxin injections.11

Pruritus is another particularly challenging aspect of EB care. Insufficient skin hydration tends to intensify itching; however, excessive moisturization may increase the risk of blister formation, necessitating a careful therapeutic balance. However, when treating pruritus in EB there has to be a balance between moisturising the skin without it becoming prone to blistering. Common treatments for pruritus in childhood EB include emollients like greasy ointments and lotions, topical corticosteroids, and oral antihistamines such as hydroxyzine. Topical emollients, including moisturisers, and bath oils are helpful. Moisturisers containing sodium lauryl sulphate should be avoided as this can exacerbate skin damage. Emerging tharapeutics option such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for severe pruritus, and pregabalin for neuropathic pain and itch, have demonstrated promising results. All treatments should be administered under the supervision of a dermatologist. Topical corticosteroids remain widely utilized for their potent anti-inflammatory properties.12,13 A few tips to protect EB children skin such as13:

- Avoid sudden changes in temperature and overheated environments where possible.

- Avoid using highly perfumed products on the skin.

- Don’t use laundry products for sensitive skin

- Clothing should be loose fitting and many people avoid products made of wool.

Maintaining optimal nutritional status is an essential component of supportive therapy in patients with EB. Nutritional management should emphasize adequate intake of energy, protein, zinc, and other micronutrients to promote wound healing, growth, and immune function. Malnutrition is highly prevalent in severe forms of EB, resulting from both increased metabolic demands associated with chronic wound repair and decreased oral intake due to blistering or scarring of the oral and esophageal mucosa. This nutritional deficiency may lead to failure to thrive, delayed puberty, and anemia—creating a cascade of clinical and biochemical consequences that further impair wound healing and exacerbate skin fragility. Serum albumin levels are often used as one of the indicators to assess the presence and severity of malnutrition. In advanced cases, patients with severe EB may require enteral nutritional support through a gastrostomy tube to maintain adequate nutritional status.14,15

Using semi-structured interviews, the primary concerns reported by pediatric patients with EB included pruritus, pain, limited participation in peer activities, social misunderstanding, and feelings of difference or isolation. Children with milder forms of EB were more affected by concerns regarding physical appearance—such as teasing, staring, and rude comments—compared to those with severe disease.6 Although EB is rare, it imposes a considerable burden on patients, families, and healthcare systems due to high medical expenses, non-medical costs, and productivity loss.4 In Europe, a survey involving 204 patients in 2012 estimated the mean annual cost per patient at €31,390 (approximately US$36,000), of which 18.0% represented direct healthcare costs, 74.8% direct non-healthcare costs, and 7.2% productivity loss.7

Management of severe EB requires a multidisciplinary approach that prioritizes wound care, optimal growth and development, and the treatment of associated complications. Effective management depends on coordinated care among specialists, including dermatologists, pediatricians and/or neonatologists, internists, anesthesiologists, pathologists, medical geneticists, pain specialists, specialized nurses, and mental health professionals such as psychiatrists or psychologists. In more complex or extensive cases, the multidisciplinary team may be expanded to include ophthalmologists, gastroenterologists, dentists, otolaryngologists, and endocrinologists. Additionally, surgical, plastic, radiological, dietary, and speech therapy expertise may be required for comprehensive care.7,8 Depending on disease severity, patients should undergo regular follow-up—at least annually—coordinated with their primary care clinician.1

Epidermolysis bullosa is a chronic genetic disorder that requires early diagnosis, continual education, and comprehensive multidisciplinary care. The primary goals of management are to minimize skin trauma, control pain and infection, maintain optimal nutritional status, and provide consistent psychosocial support for patients and their families. Advances in gene therapy and tissue engineering offer promising prospects for future treatment; however, ensuring accessibility, sustainability, and integration into clinical practice remains a critical focus for both healthcare collaboration and policy development.

References:

- Khanna D, Bardhan A. Epidermolysis Bullosa. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Updated Jan 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK599531/

- Danescu S, Negrutiu M, Has C. Treatment of Epidermolysis Bullosa and Future Directions: A Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14(8):2059–75.

- Khanmohammadi S, Yousefzadeh R, Rashidan M, Hajibeglo A, Bekmaz K. Epidermolysis bullosa with clinical manifestations of sepsis and pneumonia: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;86:1–3.

- Horn HM, Tidman MJ. The clinical spectrum of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2002 Feb;146(2):267–74.

- Hon KL, Chu S, Leung AKC. Epidermolysis Bullosa: Pediatric perspectives. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2022;18(3):182–90.

- Tabor A, Pergolizzi JV Jr, Marti G, Harmon J, Cohen B, Lequang JA. Raising awareness among healthcare providers about epidermolysis bullosa and advancing toward a cure. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(5):36–48

- El Hachem M, Zambruno G, Bourdon-Lanoy E, Ciasulli A, Buisson C, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Multicentre consensus recommendations for skin care in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:1–20.

- Vahidnezhad H, Youssefian L, Saeidian AH, Touati A, Sotoudeh S, Abiri M, et al. Multigene next-generation sequencing panel identifies pathogenic variants in patients with unknown subtype of epidermolysis bullosa: Subclassification with prognostic implications. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(12):2649–52.

- Tabor A, LeQuang JAK, Pergolizzi J Jr. Epidermolysis bullosa: Practical clinical tips from the field. Cureus. 2024;16(2):1–7

- Denyer J, Pillay E. Best practice guidelines for skin and wound care in Epidermolysis Bullosa. Internationl Consensus. DEPRA, 2012.

- Goldschneider KR, Good J, Harrop E, Liossi C, Lynch-Jordan A, Martinez AE, et al. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa research association international (debra international). Pain care for patients with epidermolysis bullosa: best care practice guidelines. BMC Med. 2014;12:1–23.

- Ludmann P. Epidermolysis bullosa: Diagnosis and treatment. American Academy of Dermatology Association. 2025 [updated: Jul 2024]. Available from: https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/a-z/epidermolysis-bullosa-overview

- Denyer J, Pillay E. Best practice guidelines for skin and wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. Internationl Consensus. DEPRA, 2012.

- Xiao A, Sathe NC, Tsuchiya A. Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita [Internet]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Updated 2023 Oct 29. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554512/

- Pope E, Lara-Corrales I, Mellerio J, Martinez A, Schultz G, Burrell R, et al. A consensus approach to wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):904–17